July 21, 2021

Massive cargo ships pose threat to critically endangered whales

Estimated reading time: 0 minutes

BY: Sarah Cameron

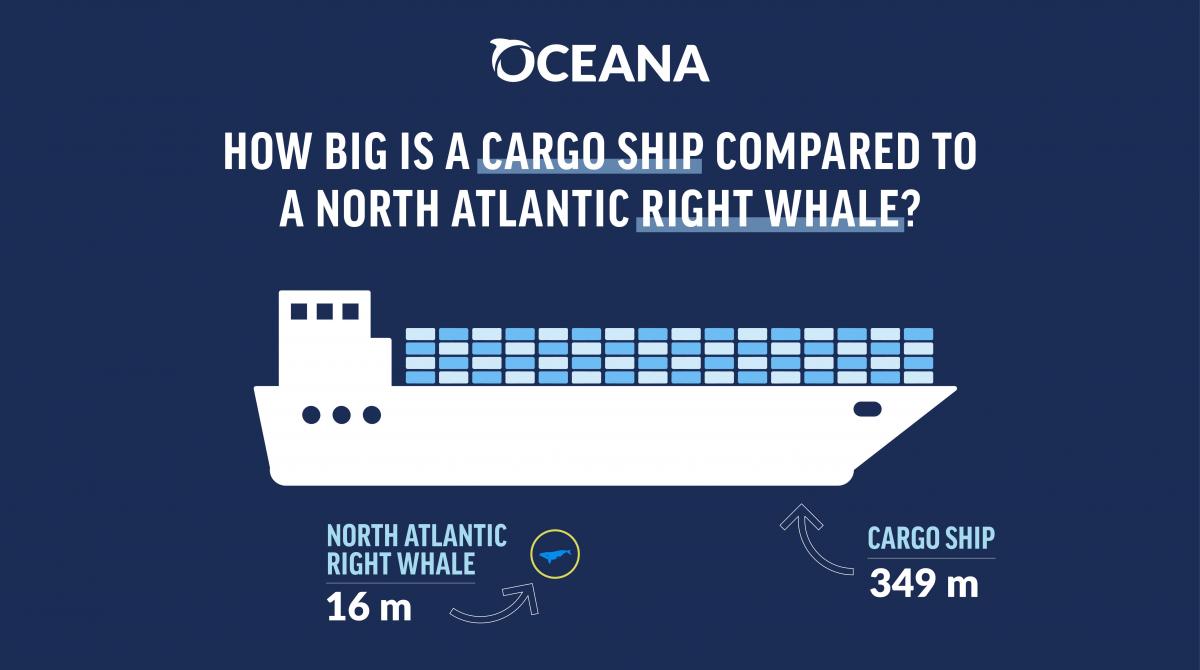

On May 17, 2021, the largest cargo ship to ever visit North America’s east coast arrived in Halifax. When we say large, we mean longer than the Eiffel Tower is tall. This ship, named the Marco Polo, has the capacity to carry more than 16,000 shipping containers. It’s absolutely massive. And giant vessels like this are the future of shipping, but is it the future that we want?

In Canadian waters, vessels colliding with critically endangered North Atlantic right whales is a well-documented issue. So much so that an array of mandatory and voluntary slowdown measures are in place to protect them. There are only around 360 right whales left because human threats caused by vessel strikes and entanglements in fishing gear are decimating their population.

With so few right whales left, sighting one is rare. However, on May 17, 2021, the day of the Marco Polo’s journey into Halifax, a North Atlantic right whale was spotted on the Scotian Shelf in the exact same area the vessel was travelling.

How fast is too fast?

When a vessel strikes a whale, the results are often fatal but usually serious; they are either killed by the sheer force of the vessel strike, or they are severely injured, sliced and scarred by the vessel’s propellers. Research has shown that pregnant whales and mothers with calves may be more susceptible to ship strikes because they spend more time resting and nursing at the surface.

Although there is no absolute safe speed for vessels to travel, we know that when they travel at slower speeds, whales have a greater chance of surviving a strike. Research has shown that mandatory season-long speed limits of 10 knots in certain areas reduced the risk of lethal collisions by 86 per cent. At speeds of 20 knots or more, right whales have little chance of surviving a collision. In a recent study researchers also found that vessels of all sizes have the potential to cause lethal injuries to whales and that the risk increases significantly as the size and weight of the vessel increases. This was tragically proven in February, when a right whale calf was killed by a sixteen-metre-long recreational fishing boat traveling at 21 knots (approximately 40 km/h) off the coast of Florida.

But the Marco Polo is a huge vessel – only four metres shorter than the Ever Given that was stuck in the Suez Canal for six days earlier this year. When the Marco Polo was in Canadian waters and travelling through critically endangered right whale habitat, it was travelling at an average speed of 18 knots*. If a giant vessel travelling at such high speeds were to hit a whale, the outcome would very likely be fatal. Fortunately, the right whale that was on the Scotian Shelf that day in May wasn’t struck.

Ships need to slow down

Since 2017, at least 33 right whales have been killed – 21 of them in Canadian waters. Of these, there were 10 cases where a cause of death could be determined and eight of which were related to ship strikes.

Canada needs to do everything possible to protect critically endangered right whales from extinction. Right now, there is a voluntary slowdown zone in the Cabot Strait which asks vessels to slow down to 10 knots. In 2020, it was ignored by two-thirds of the vessels travelling through the Cabot Strait. Despite the persistent non-compliance – and Oceana Canada sharing its findings with Transport Canada throughout 2020 – the measure has remained voluntary in 2021.

The Marco Polo was the first of likely many massive cargo ships that will be visiting Canadian waters. If we don’t want to see North Atlantic right whales go extinct in our lifetime, vessels of all sizes need to slow down, and measures need to be made mandatory. It is literally life and death.

*Oceana Canada obtained the speed of the Marco Polo using Global Fishing Watch data.

Global Fishing Watch, a provider of open data for use in this article, is an international nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing ocean governance through increased transparency of human activity at sea. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors, which are not connected with or sponsored, endorsed or granted official status by Global Fishing Watch. By creating and publicly sharing map visualizations, data and analysis tools, Global Fishing Watch aims to enable scientific research and transform the way our ocean is managed. Global Fishing Watch’s public data was used in the production of this publication.