September 23, 2022

A Hazardous Move: Insufficient Protection for the North Atlantic Right Whales

Estimated reading time: 0 minutes

Between 2017 and 2019, an “unusual mortality event” was declared for one of the most endangered whale species in the world – the North Atlantic right whale. Those years brought a devastating and unprecedented number of deaths – 34 known in total with an astounding 21 whales found dead in Canadian waters. Today there are only around 330 individual right whales left. The greatest threats to their survival? Vessel strikes and entanglements in fishing gear.

Up until recently, North Atlantic right whales could be found in the Bay of Fundy from April until November, where many whales would migrate annually to summer feeding grounds. However, climate change and warming ocean waters have caused their favourite prey – copepods, or tiny crustaceans – to move further north into the Gulf of St. Lawrence and surrounding waters. The whales now follow their food into this area every summer – an area with many annual measures to protect them but nothing that is permanently in place to safeguard them from the risks of vessel strikes and entanglement in fishing gear.

Of the 21 right whales killed in Canadian waters between 2017 and 2019, the cause of death could only be determined for 10 cases. Eight of those deaths were caused by blunt force trauma from collisions with vessels. The faster a vessel, or ship, travels, the less likely it is for a whale to survive a collision. Slowing down to 10 knots can greatly reduce the risk of serious injury and death to right whales. In fact, some research demonstrates that this reduction in vessel speeds can reduce the lethality of a collision by 86 per cent.

Make 10 Knots Mandatory

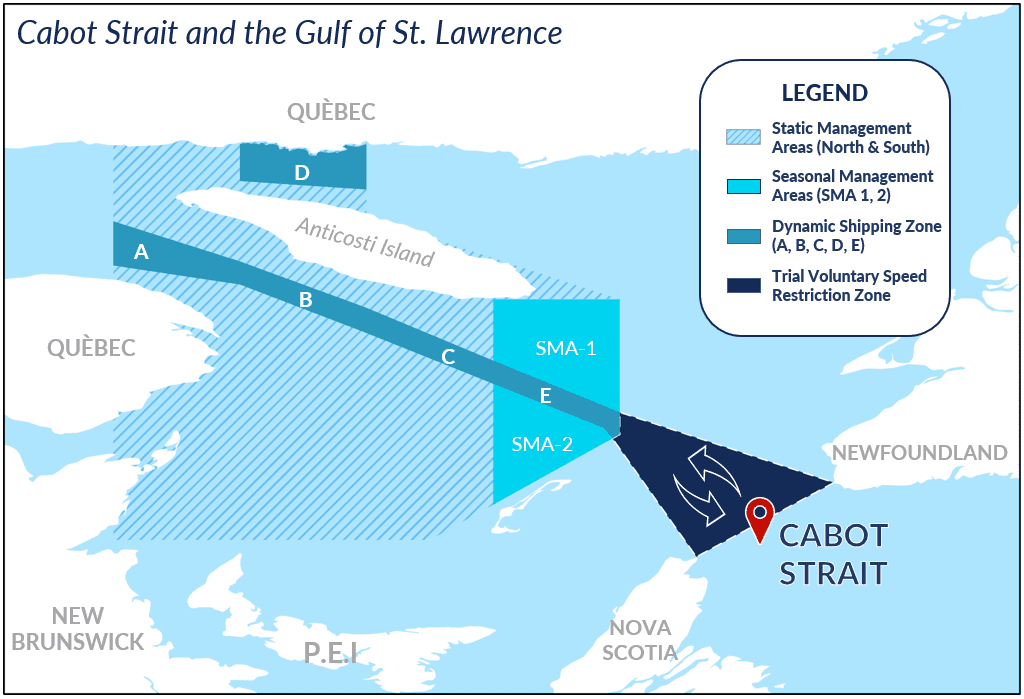

While on route north during their summer migration, right whales have no other path into the Gulf of St. Lawrence than through the Cabot Strait – the primary corridor into the Gulf of St. Lawrence as well as a busy shipping route. During the season whales are in Canadian waters, protecting this path into the Gulf is a no-brainer.

In 2020, a 10-knot speed restriction zone was created on a trial basis in the Cabot Strait, with the goal of protecting right whales from ship strikes. The problem? This speed restriction zone is voluntary – meaning vessels are not legally required to slow down. In an industry where getting products from point A to point B as quickly as possible is seen as advantageous, vessels that do slow down to the recommended 10-knot speed limit are often at an economic disadvantage. Additionally, the slow-down period only lasts for about 10 weeks each spring and fall and is not active throughout the entire time whales are in Canadian waters.

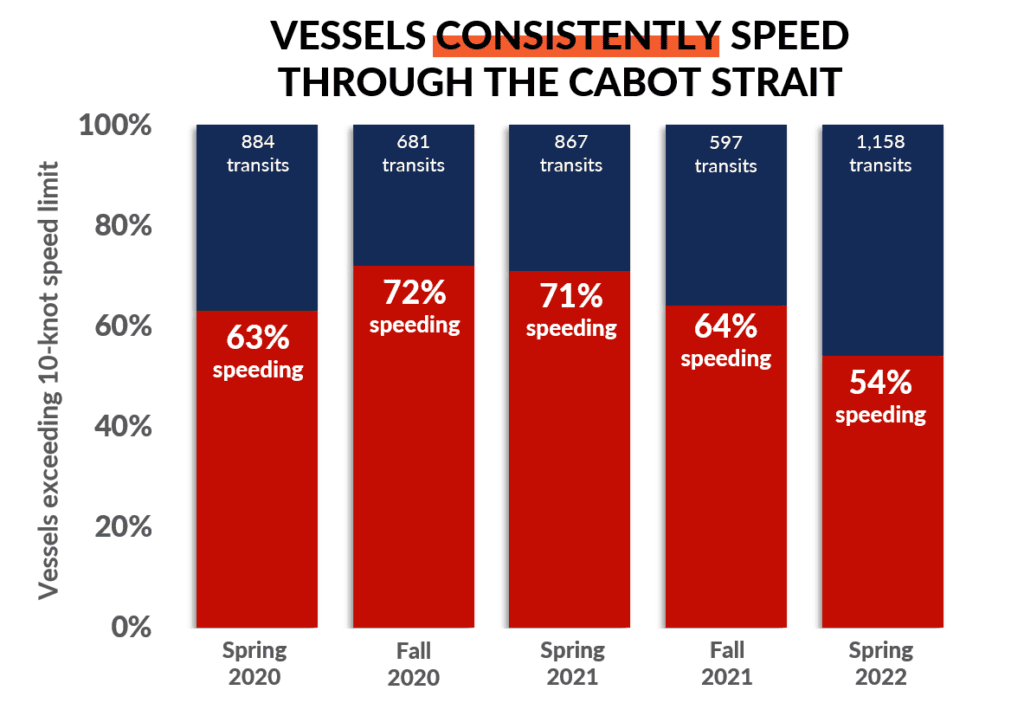

Oceana Canada tracked vessel speed compliance in the Cabot Strait speed restriction zone since 2020, using satellite data from Global Fishing Watch. Disappointingly, the rate of compliance with the 10-knot speed limit was far too low for this voluntary measure to be considered successful. Each time the voluntary slowdown measure has been in effect, we found that at least half – and up to nearly three quarters – of all transits recorded in the Cabot Strait were found exceeding 10 knots, some even traveling at double the recommended speed.

North Atlantic Right Whales need your help

Now, after three years of very poor compliance, Transport Canada is making a decision about the future of the Cabot Strait protection measures. Oceana Canada is calling on it to take immediate action and install season-long and mandatory speed restriction zones in the Cabot Strait. It’s time to manage vessel speeds when and where critically endangered North Atlantic right whales are present – before it’s too late.

MOST RECENT

April 24, 2025

March 6, 2025

February 3, 2025

January 22, 2025

Celebrating New Beginnings in 2025: Four Right Whale Calves Spotted Off Florida Coast