May 9, 2018

Deep sea expedition highlights value of partnerships for marine conservation

Estimated reading time: 0 minutes

BY: Oceana

Topics: Protect Marine Habitat

Originally posted by Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance (CCIRA).

On a March morning this spring, a group of scientists, educators, traditional knowledge holders, and resource managers gathered around a collection of screens on board the Canadian Coast Guard vessel Vector, with coffee cups in hand. They were tired from long days of work, but also excited about the day ahead. Cruising 400 meters below them was “BOOTS”, a high-tech drop-camera equipped with lights, lasers, and numerous sensors. As Vector towed BOOTS along, its cameras beamed video footage from the depths onto the ship’s numerous screens, while a high-tech satellite connection live-streamed the footage to eager eyes via the internet.

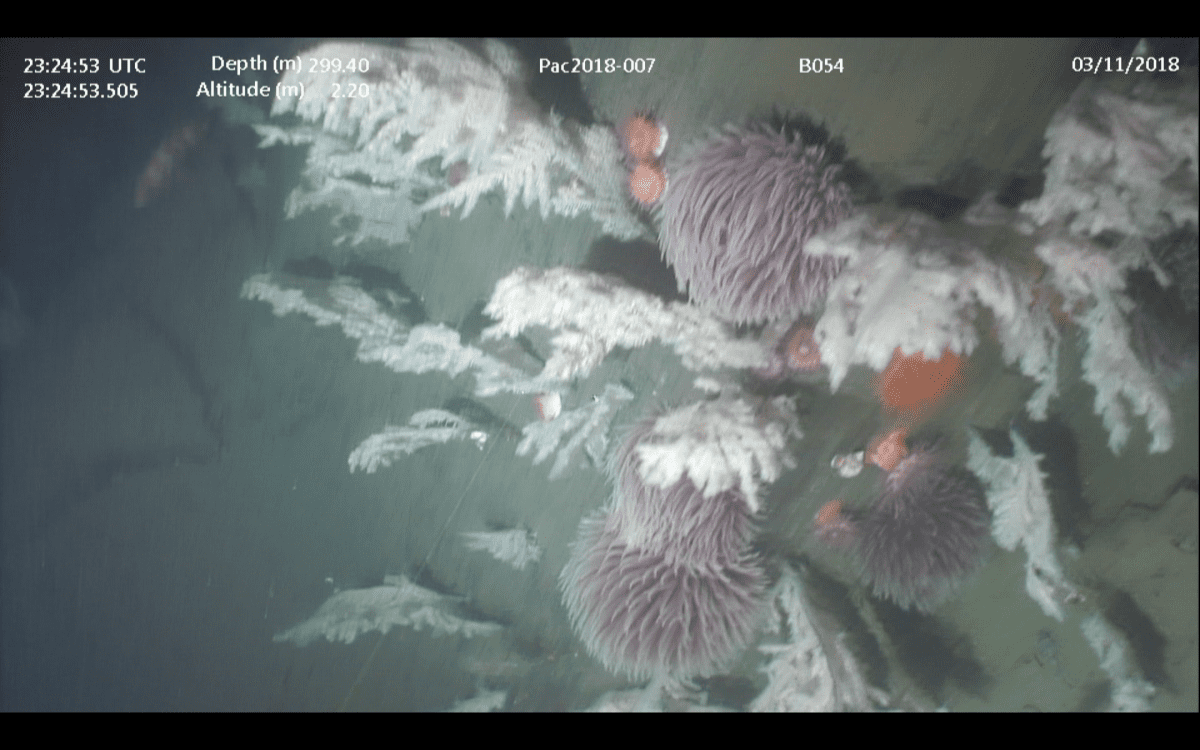

Out of nowhere, a pom-pom anemone appeared on a screen. Pink, frilly and shaped something like a cheerleader’s pom-pom, it is a rarely observed species that can live at depths up to 3000m. Sometimes called a tumbleweed anemone, this creature is known to get “blown” across the sea floor by ocean currents.

The pink anemone was an extraordinary sight against the backdrop of the dark seafloor. Then another one came into view, and another. “All of a sudden the screen was filled with them,” says Barry Edgar, Marine Planning Coordinator for the Kitasoo/Xai’Xais Nation, who watched the live video feed from Klemtu. “I’d never seen anything like that. It was pretty amazing.” This was just one moment of discovery during a recent deep-sea research expedition in Central Coast waters.

Drop camera photo of pom-pom anemones and black corals at a depth of 300 metres (Oceana Canada/Evermaven)

Canadian Coast Guard vessel Vector at work in the Central Coast of British Columbia (Oceana Canada/Evermaven)

Canadian Coast Guard vessel Vector at work in the Central Coast of British Columbia (Oceana Canada/Evermaven)

CCIRA and the Kitasoo/Xai’Xais and Heiltsuk Nations, partnered with Oceana Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), and Ocean Networks Canada on this project that aimed to gather new data on never-before-studied parts of the Central Coast. The primary goal was to help inform the marine conservation work already underway. But something else unexpected happened; a synergy between the expedition partners emerged, and the project set an example for how multi-culture, multi-disciplinary collaboration can contribute to common marine conservation goals.

Over the course of nine days, Vector performed a total of 17 tows, with BOOTS at depths between 200 and 550 metres. The longest tows lasted up to three hours and covered several kilometres, exploring areas of high ecological, cultural and economic significance, including Kynoch Inlet, Seaforth Channel and Fitz Hugh Sound.

“We know what is above the water everywhere we go in our territory,” says Barry. “We know all the traditional stories and have a lot of traditional knowledge of all the places we travelled during this expedition. But we’ve never seen the seafloor at these depths before – this was uncharted territory for us.”

“We know all the traditional stories and have a lot of traditional knowledge of all the places we travelled during this expedition. But we’ve never seen the seafloor at these depths before – this was uncharted territory for us.” Kitasoo/Xai’Xais Marine Planning Coordinator Barry Edgar.

Our Nations have been probing the depths with fishing gear for millennia and more recently with our own research. “The Nations’ research has taught us a lot about Central Coast rockfish,” says CCIRA’s Science Technician, Tristan Blaine. CCIRA’s research team has assembled the biggest dataset of rockfish size and abundance ever created for the inside waters of this region. But, says Tristan, the inability to sample deeper than 200 metres has left unanswered questions. “During this expedition, we got well beyond the 200-meter mark, which provided some great new insights.”

In some places the team found rockfish species that were unaccounted for in CCIRA’s previous research. “We had been a bit puzzled by the absence of these species because the Nations’ fishermen had detailed stories about them. This new information starts to fill in some gaps in our data and will help us refine our research while contributing to conservation planning.”

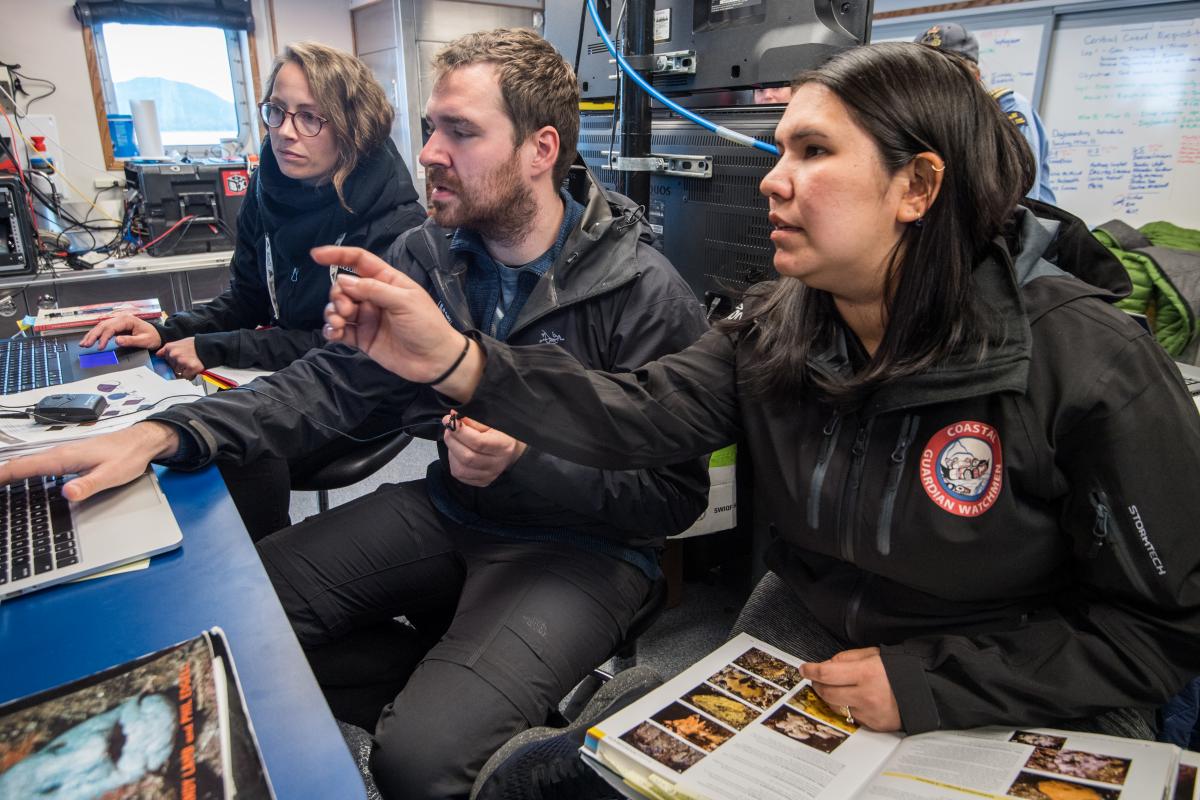

(left to right) DFO scientist Lily Burke, CCIRA’s Science Technician Tristan Blaine, and Desiree Lawson of the Heiltsuk Nation watching live video from BOOTS on board Vector (Oceana Canada/Evermaven)

New insights into rockfish at greater depths were just one of many new observations. As BOOTS combed the ocean floor, it also collected footage of numerous other deep-water species, spotting large halibut, huge schools of skates, soft corals, and glass sponges.

Until a reef of living glass sponges was discovered in Hecate Strait in 1987, they were only known to science from the fossil record. “Reef-building glass sponges were thought to be extinct,” says Tristan. “But they live right here in BC waters.” These are really slow-growing and long-lived animals. The Hecate Strait reefs have been aged at nine thousand years. They provide habitat for numerous species, act as carbon sinks and cleanse the water of bacteria and viruses.

DFO studies have shown that glass sponge reefs can be important habitat for spot prawns, herring and rockfish; reefs have been shown to have ten times more juvenile rockfish than surrounding areas.

Like glass sponges, soft corals are slow-growing and provide habitat for other species. Feathery, beautiful and fragile, these creatures are out of sight and unknown to many people. During previous research, Tristan watched as a prawn fisherman pulled up his gear with soft corals all over it. “This is a great example of why we need to do this work,” he says. “Many people don’t know what’s down there and they are causing environmental damage to these irreplaceable glass sponges and corals and they don’t even know it.” The data from this expedition, he says, can help map out some of these key features so they can be protected more effectively.

(left to right) Oceana Senior Advisor Alexandra Cousteau, DFO Minister Dominic LeBlanc, and Oceana Canada’s Director of Science Bob Rangeley (Oceana Canada/Evermaven)

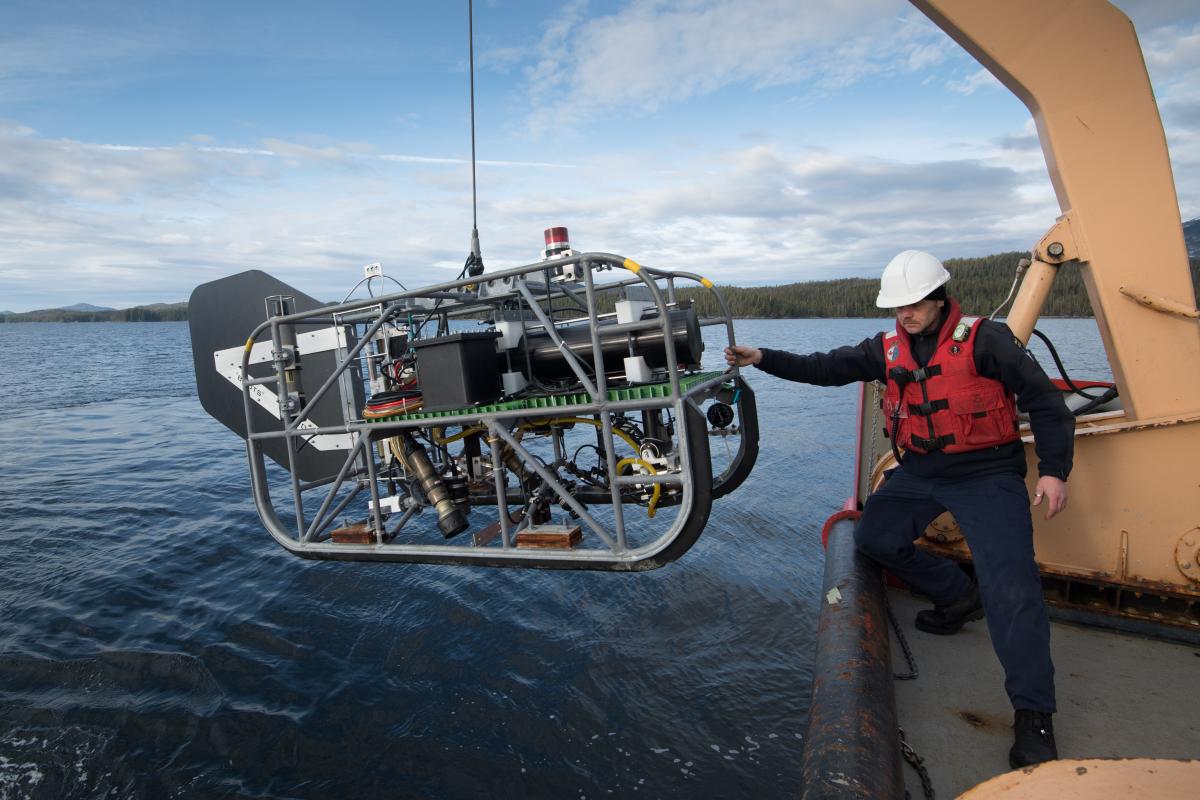

Back on Vector’s deck between tows, Tristan watched technicians fussing over BOOTS, replacing cameras, adjusting lasers and settings, and re-pressurizing the rig to enable dives to great depths. The process took an hour before and after each tow. “We could never do this scale of research on our own,” he laments. “That is the value of partnerships like this.”

Collectively the expedition pulled together the most diverse group of expertise ever assembled for a research project on the Central Coast. Notable filmmaker and Oceana Canada’s Senior Advisor Alexandra Cousteau–the granddaughter of famed ocean explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau –was on board, as was Minister LeBlanc from the DFO.

“It was really great to see that level of engagement from all the partners and Minister LeBlanc,” says Tristan. But, he says, the most interesting part of the expedition–other than the science–was witnessing how all the other partners recognized the deep expertise of the local people.

The Director of Science from Oceana Canada, Bob Rangeley, was part of the research crew. With over 1000 research dives under his belt, he is no stranger to the ocean. For Bob, this collaboration with the Nations provided some fresh perspectives.

“The Nations brought a level of understanding of the local ecosystems that we would never have had if we just jumped on a boat and started dropping cameras,” he explains. “This project was building on a foundation of knowledge that the Nations already have from their research and traditional knowledge.”

“The Nations brought a level of understanding of the local ecosystems that we would never have had if we just jumped on a boat and started dropping cameras…it really was a two-way learning experience. This collaboration has the potential to be conservation at its best.” Oceana Canada Director of Science Bob Rangeley.

In Klemtu the research team was invited into the Bighouse with its giant Sitka spruce beams and towering carved poles representing the different clans of the Kitasoo and Xai’Xais Nations. While inside, they listened to some stories told by the local people. “At that moment,” says Bob, “it really dawned on me that when we talk about the sustainable use and conservation, this is how it will be achieved–through this deeper level of knowledge and long-term stewardship that these Nations have. These people are not going anywhere, and they have a long, deep connection with the ocean, which is something that is pretty special. Without this collaboration, I don’t think I would have appreciated that in the same way.”

What Bob and others on the team were tapping into is our Nations’ deep history here. Recent archaeological evidence suggests that our people have occupied this area for at least 14,000 years. And although Central Coast populations were significantly higher in the past than today, our people historically managed marine resources sustainably using our own complex management practices that are rooted in thousands of years of traditional knowledge. For marine resources in our territories to recover from the industrial fishing practices of the last 100 years, our Nations believe we need a network of marine protected areas that embrace our resource management principles and cover a significant portion of our territories.

Kitasoo/Xai’Xais SEAS Coordinator Vernon Brown and Brock Edgar contemplating a yelloweye rockfish (Oceana Canada/Evermaven)

After leaving Klemtu, Vector sailed into Heiltsuk territory. When Heiltsuk local, Desiree Lawson, stepped on board at 8 am one morning, she was overwhelmed at first. “They had so much equipment and so many monitors. It was all pretty intense.” But before long she was making discoveries of her own, watching those monitors and learning from the biologists how to identify the species on the screen. “I was born and raised here and have a strong connection to my territory, so it was really fun to see all these species I’d never seen before.”

Desiree works with the Revitalizing Indigenous Laws for Land, Air and Water (RELAW) Project in Heiltsuk territory. “I keep learning more and more about how people from different experiences, perspectives and backgrounds can work together to protect our oceans now and for the future,” she says. “All the partners on this project were looking at marine conservation challenges through the eyes of their different experience, but we shared the common objective of protecting ocean resources.”

The experience evoked a teaching that was instilled in her from Heiltsuk knowledge-keeper and teacher, Pauline Hilistis Waterfall. “Pauline taught us to recognize that, regardless of who people are and where they are from, our similarities are greater than our differences.” For Desiree, this is a powerful message that resonates with her experiences on this project. “There is so much we can learn from each other.”

“BOOTS” being deployed at the stern of CCGS Vector (Oceana Canada/Evermaven)

Bob agrees. “It really was a two-way learning experience. This collaboration has the potential to be conservation at its best.” In his view, the vested interest of the Nations translates into commitment and responsibility, which is critical for marine conservation projects. “To be involved in such a profound way with communities that are so invested in long-term stewardship is really gratifying,” he explains.

While the expedition is now over, the project is not. “The analysis, results, and the final recommendations are yet to come,” says Bob. “Ultimately, we need to translate all of this data into policy and management changes and protected areas that make a difference on the water.”