September 29, 2021

The Inexplicable Rise of Redfish

Estimated reading time: 0 minutes

BY: Emily Petsko

Topics: Rebuild Ocean Abundance

Originally published in Oceana Fall 2021 Magazine

In Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence, one fish, two fish – millions of fish – are redfish. Luck may have helped revive this once-endangered species, but will science keep them around? “Luck” is not a word you hear often in fisheries management. And yet, it’s a word that Caroline Senay, a federal biologist with Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), uses to explain the redfish bonanza in Atlantic Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence. Much like Atlantic cod, redfish are a groundfish species that succumbed to overfishing in the mid-1990s and collapsed, forcing a fishery closure. They were even classified as endangered as recently as 2010.

Unlike cod, redfish rebounded. From 2011 to 2013, the Gulf’s redfish population had a massive recruitment, scientific lingo meaning more redfish than usual survived past the larval stage. They kept getting bigger and bigger, and by 2019, redfish accounted for 90% of the total biomass – or collective weight – of everything DFO caught in the northern part of the Gulf during its annual survey of marine life on the seafloor. Previously, redfish made up only 15%.

Researchers say environmental changes may have worked in their favor, like warmer temperatures (which redfish seem to prefer) or an abundance of zooplankton (which redfish eat). A redfish moratorium in one area of the Gulf – called Unit 1 – also set the stage, allowing redfish to recover when the conditions were right. The moratorium has kept fishing pressure low since 1995, allowing only limited amounts for research and monitoring purposes.

As redfish grow, so does interest in lifting the moratorium. However, Oceana and other groups are urging caution and proper planning. Senay compared the scenario to hitting the jackpot: The windfall is nice, but what happens if the money runs out? “We’ve been lucky. We have this huge amount of redfish, and we don’t know when we’re going to win the lottery again,” Senay said. “We need to plan our harvest assuming that we might not have another strong recruitment for 10, 15 years. And if we’re lucky again, we’ll reassess how much money we have in our bank account and we’ll be able to ‘spend’ more, or fish more.” Luck may have played a role in rejuvenating redfish, but if we want to see a truly abundant and longlived redfish fishery, proponents say science-based fisheries management is the best chance we have.

From processing plant to parking lot

Redfish are sometimes called “ocean perch,” even though they aren’t perch at all – they’re rockfish. The name arose in the 1930s, when a fish cutter discovered that redfish were similar in taste and texture to freshwater perch, a popular species in some areas. Harvesters started rebranding redfish as ocean perch and offering it as a substitute.

So what exactly does redfish taste like? Dr. Kris Vascotto, executive director of the Atlantic Groundfish Council, likened its flavor to that of a lake trout or a Pacific ocean perch (another type of rockfish). “It’s an oily fish with a very light-colored fillet. It’s not a cod, it’s not a halibut, and it’s not a haddock,” he said. “It’s not the type of thing that you’re going to batter or fry. Generally, what I’ll do is grill it in my pizza oven with some sesame oil and light soy sauce on it, and it’s absolutely divine.”

Despite Vascotto’s taste for redfish, it’s not a popular or well-known fish in Canada. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, redfish were primarily exported to the United States, and many fillets ended up being served in military cafeterias because they were a consistent size and fairly inexpensive. Even though redfish didn’t win over Canadian palates, it did support local processing jobs, especially in the Gulf of St. Lawrence region. Many types of seafood – including lobster and other shellfish – are exported and processed abroad (often in China), then shipped back to North America. But redfish were historically processed in Canada, then exported to other end markets. When redfish collapsed, many of those local processing plants shut their doors for good.

“A couple years ago I went to check out some of the old processing plant sites where the redfish fisheries were,” Vascotto said. “Now they’re basically just parking lots in these little communities that are now supporting lobster fisheries.”

Under most rebuilding scenarios, a redfish fishery would generate a higher landed value than the status quo, according to an Oceana commissioned analysis by Dr. Rashid Sumaila and Dr. Louise Teh from the University of British Columbia. This, in turn, could help boost local economies and bring back jobs that were previously lost.

Vascotto expressed “cautious optimism” that the Unit 1 moratorium will be lifted someday but said it should not be rushed. Redfish are more valuable once they reach a size that’s suitable for fillets – roughly around 30 centimeters – and the fish are currently around 23-24 centimeters. To ensure this fishery is both profitable and long-lasting, it needs to be sustainable, he said. Of course, figuring out how to effectively manage redfish comes with its own set of challenges.

Management status: It’s complicated

Redfish, despite what Dr. Seuss may lead you to believe, are not so simple to identify. There are actually two species of redfish in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and they look identical to the untrained eye. Deepwater redfish (Sebastes mentella) are healthy and flourishing. Acadian redfish (Sebastes fasciatus) are significantly fewer in number, relegated to the “cautious” zone.

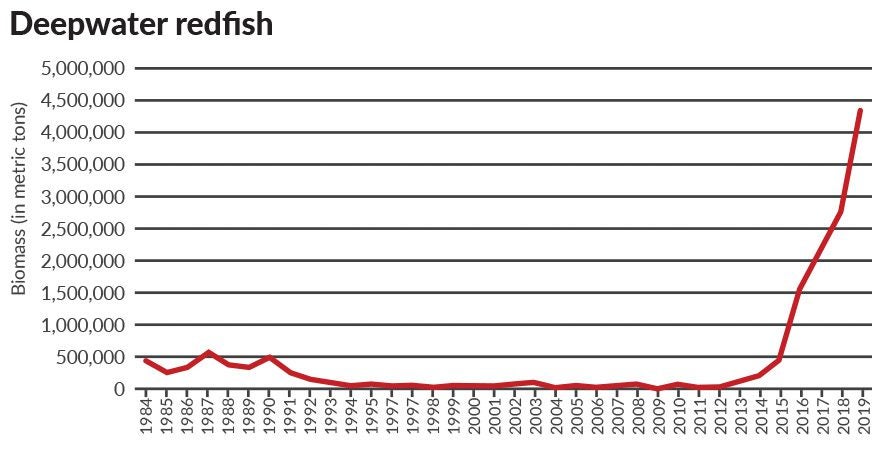

DFO surveys found that there were 4.4 million metric tons of redfish in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 2019 –the highest biomass for redfish on record. But if you break that down further, you’ll see that Deepwater redfish dominate the landscape, accounting for 4.363 million metric tons.

This is great news for Deepwater redfish, but it poses a challenge. Oceana asserts that a sustainable fishery would be able to target Deepwaters while avoiding Acadians, but the main way to tell them apart is by counting the number of soft rays in their anal fin. This so-called “species split” takes some time to master, but onboard observers have been successfully trained in this technique.

The other obstacle is finding a highly selective gear that doesn’t catch and kill a considerable number of non-targeted species, otherwise known as the bycatch rate. Ideally, the gear would avoid Acadian redfish and other depleted species, like white hake and cod, as well as commercially valuable species like halibut.

These are questions that Dr. Erin Carruthers, a fisheries scientist with the Food, Fish & Allied Workers union (FFAW-Unifor), has been grappling with for some time. The union represents Newfoundland harvesters who catch redfish in the fisheries where it’s permitted, including a three-year experimental fishery designed to test out different gears and tactics.

Midwater trawls, which avoid scraping the seafloor, have shown promise in reducing the bycatch rate to 2%. However, they really only work in the winter months, when redfish are higher up in the water column, Carruthers said. Newfoundland-based harvesters have also been testing ways to reduce impacts on the seafloor and other sea life, including a modified net that allows non-targeted fish to swim through escape vents before it’s hauled up to the surface. “What we’re working on with the experimental fishery is how to fish sustainably and how to have a longterm redfish fishery,” Carruthers said. “I think it will take a couple more years for us to really square away this species split and the gear type.”

Slow and steady

Oceana has been advocating for science-based management of the redfish fishery and supports DFO’s decision to keep existing redfish quotas low until a more robust plan is in place. “The current redfish biomass boom is an incredible opportunity for a re-emerging and expanded fishery, but not if we don’t have a good plan to manage the complexities of the bonanza,” said Devan Archibald, a fisheries scientist for Oceana Canada. Archibald said that plan should include strategies to prevent bycatch of undersized Deepwater redfish and less abundant Acadian redfish, along with other species that are depleted or commercially valuable. Attention should also be given to protecting sensitive benthic habitats in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, some of which Oceana identified during its 2017 expedition.

Pressure to raise redfish quotas or lift the moratorium will likely mount in the coming year as redfish mature and reach a more marketable size. However, this is our chance to take it slow and work out the logistics, Archibald said. This species is slow-growing and incredibly long-lived, so there’s even more of an incentive to make sure redfish stick around – for good this time. “They can live 75 years,” Senay said. “If I do my job well, I’ll retire and some of them will still be swimming happily in the water.”