June 3, 2016

Guppy Love: 5 of the Weirdest Ways Marine Animals Reproduce

Estimated reading time: 0 minutes

BY: Allison Guy

Topics:

Love is a many-splendored thing, and nowhere is it more splendid — or strange — than in the ocean. For marine animals, reproduction involves not just romance, but also fencing, sex change and cannibalism. From worms to whales, the mating strategies of these five animals are among the strangest in the sea.

5. Marine flatworms: Dueling for pregnancy

Like other marine flatworms, the Persian carpet flatworm has a violent mating strategy. Hans Gert Broeder / Shutterstock

Marine flatworms in the genus Pseudobiceros come in a riot of colors — one species is aptly named the “Persian carpet flatworm” — but their sex lives might be even more colorful.

Each worm is a hermaphrodite, and comes equipped with two penises. When a pair of amorous worms meet, they “fence”with their penises, each attempting to inject sperm into their partner while avoiding getting inseminated themselves. These duels, which can last up to an hour, are so rough-and-tumble that both worms may suffer from permanent stab wounds.

In these contests, the victor is the worm that succeeds in injecting its partner first. Not only does the winner end up “fathering” more offspring, it also ends the encounter with fewer wounds to heal. The loser limps away injured and with more fertilized eggs to carry.

Researchers think flatworms evolved this elaborate sexual battle because being pregnant comes at a high cost in terms of energy and effort. The deadbeat dad, by comparison, gets away with investing minimal resources in the next generation.

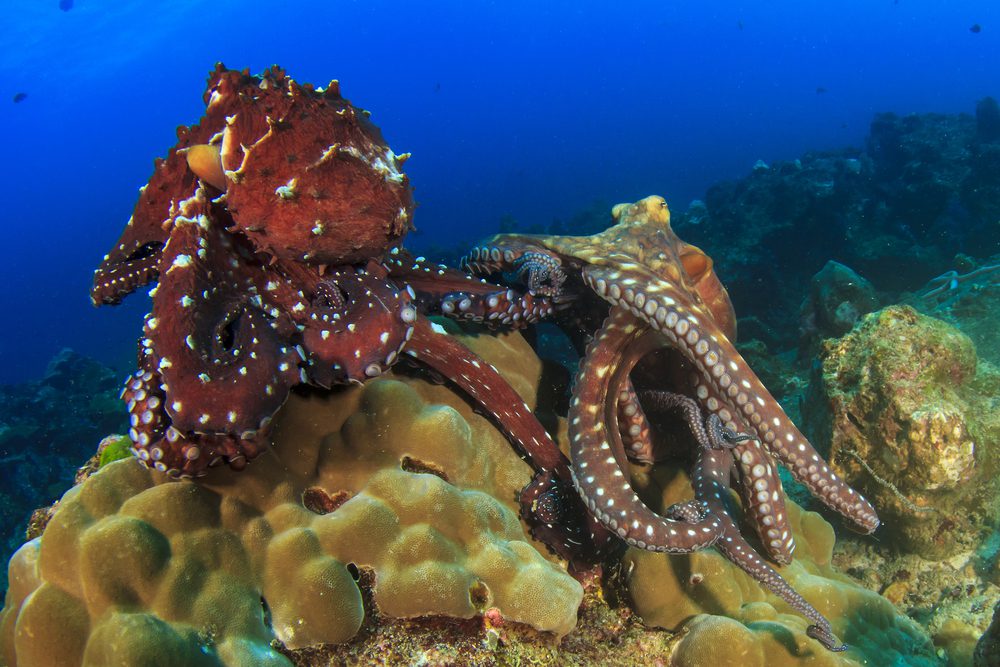

4. Larger Pacific striped octopus: Mating beak-to-beak

Sexual cannibalism has been observed several times among octopuses. But one little-studied species is a lover, not a fighter. Rich Carey / Shutterstock

The typical octopus leads a solitary life, and for good reason. Cannibalism among these cephalopods is relatively common, and sexual cannibalism has been observed on several occasions.

In Palau, one female big blue octopus (Octopus cyanea) mated with a male 13 times and then strangled and ate him. Over at the Seattle Aquarium, the 2016 Valentine’s Day mating for its giant Pacific octopuses was scrapped over fears that the enormous male might prefer to devour his date.

Amid all this violence is the peacenik larger Pacific striped octopus, a species so little-studied that it has yet to receive a scientific name. What we do know about these eight-legged wonders is remarkable: Males and females have been observed sharing dens, possibly feeding each other, and mating in an intimate “beak-to-beak” embrace. They can also form colonies of up to 40 individuals.

And, while most female octopuses die soon after their eggs hatch — and the males die soon after mating — the larger Pacific striped octopus lays clutches of eggs for up to six months. This gives them multiple mating opportunities where their cousins have just one.

3. Palolo worms: When the moon hits your eye like a big mucus pie

When the timing of lunar cycle is just right, swarms of palolo worms (Palola/Eunice viridis) rise to the sea’s surface on coral reefs ranging from Indonesia to the South Pacific. As the worms spiral upwards they burst apart, releasing gooey clouds of eggs and sperm.

These “risings” are a cause for local festivities. The gelatinous worms can be fried, baked or eaten raw, and reportedly taste like caviar.

Until the late 1890s, it was a mystery why these worms have light-sensing eyespots but no eyes, mouths or even heads. It turns out that the part of the worm that participates in the annual risings is only half the story. The other half — the part with the head — stays safely tucked away in hard corals and rocks.

Before it’s time to spawn, the worm grows a special segment on its backside that becomes filled with eggs or sperm. Then, based on cues from the moon, its rear end breaks off and floats towards the surface to get fertilized.

2. Bluebanded goby: It’s good to be king, then queen, then king again

For a bluebanded goby, it may be easier to change sex than find a new home. Peter Liu Photography on Flickr

Many species of fish are born one sex and switch to another depending on their size, age or social status. This change is almost always a one-way-street — except when it comes to certain tropical gobies.

Bluebanded gobies (Lythrypnus dalli) are highly social, living in crowds with up to 120 fish per square yard. Each group is headed by a dominant male, with a size-based hierarchy of several females below him.

For these gobies, it’s good to be king. A male goby has many more opportunities to pass on his genes than a female, who is limited by the number of eggs she can lay. But sometimes a queen can become a king. When the male dies, the biggest female in the group will change sex and take on the role of her departed partner.

In the event that a group of males find themselves with no females handy, they have the extraordinary ability to revert back to being female. The smaller, more submissive fish switch their testes out for ovaries, while the dominant fish wins the reproductive “prize” of remaining male.

This sexual shape-shifting might seem like overkill — after all, a male fish could presumably swim off in search of a female. But bluebanded gobies are territorial. On coral reefs, where real estate is at a premium, there can be fierce competition for the small nooks that can keep gobies safe from predators. For these fish, it may be easier to change sex than to find a new home.

1. Right whale: A testament to testes

Female right whales only give birth once every few years — leading to oversized competition between males for fatherhood. Mogens Trolle / Shutterstock

The three species of right whale are not the world’s largest animals — that distinction falls to blue whales — but they do set a size record in another regard. Male right whales have the largest testicles of any creature on earth, each weighing about 1000 pounds (500 kg). These gargantuan gonads are also proportionally larger than what would be expected based on their owner’s body size.

These outsize testicles are the odd result of right whales’ relatively peaceful nature. Males of these species rarely fight over females, a surprising finding given that male-on-male violence is the rule rather than the exception in mammals.

Instead, most of the “fighting” occurs inside the female’s reproductive tract. Female right whales are highly promiscuous — they’ve been spotted being courted by anywhere from two to more than 40 suitors — but they only give birth to one calf every few years.

Faced with sporadic shots at fatherhood, males have evolved to produce big quantities of sperm. The more sperm a male makes, the better chance he has to pass on his genes.

As these five creatures prove, making love can look a lot like making war — but tenderness can be found in the most unexpected places. Next time you give a wedding toast, dispense with the humdrum “lovebird” comparisons, and instead wish the newlyweds a lifetime of love like a larger Pacific striped octopus.