January 27, 2023

Spotlight on the seas

Estimated reading time: 0 minutes

Topics:

How Oceana uses Global Fishing Watch to conserve the oceans.

In July 2018, the Spanish government fined two fishing vessels for “going dark,” aka disabling their automatic identification system (AIS) for more than 1,000 hours over several years. Turning off AIS — the device that shares a ship’s direction, speed, location, and identification every 2 to 30 seconds — is dangerous, as these transmissions help prevent vessel collisions and promote transparency of fishing operations.

So how did the Spanish government know to call out these two bad actors when there are thousands of Spanish-flagged vessels out at sea? They were alerted about the questionable behavior by Oceana, which used Global Fishing Watch’s public map to track the ships’ whereabouts.

María José Cornax conducted similar investigative work by hand many years ago. While a campaign manager at Oceana in Europe, Cornax tediously tracked the movements of a single Spanish vessel by its AIS transmissions. Oceana’s Chief Policy Officer, Jacqueline Savitz, recalled Cornax plotting the ship’s location every hour, using the dots created on the map to determine whether it was fishing or transiting. Her efforts led to an illuminating find: The vessel was fishing in an area where it did not have a license to operate.

Soon after, a Google staff member told Savitz they could get AIS data. That’s when Savitz had a lightbulb moment. What was taking Cornax months to do — tracking a fishing vessel’s activities hour by hour — could actually be done very quickly by computers. And not just for one boat, but also for all other AIS-transmitting boats globally. “I remember emailing her afterwards and listing all the things we could do if we had those data. We could see when people were fishing in places they weren’t supposed to be, like marine protected areas, or fishing for things they weren’t supposed to be fishing for.”

Savitz soon found herself in a meeting with Google and SkyTruth, a nonprofit using satellite data to monitor environmental threats. SkyTruth’s team had a similar idea to Savitz’s. Together, the trifecta created Global Fishing Watch in 2016, an independent nonprofit that provides a free and easy online tool that uses satellite technology to give the public an unprecedented ability to view and track commercial fishing activity worldwide.

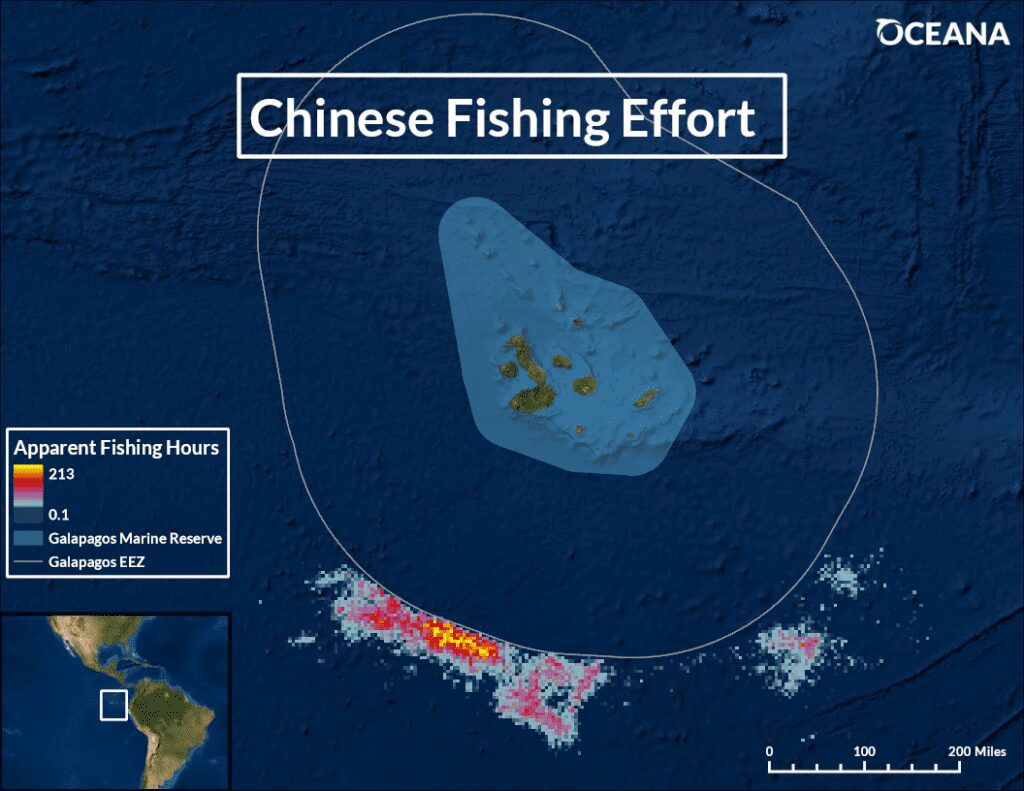

Since its inception, Oceana has used the Global Fishing Watch platform to identify fishing trends at sea and spotlight bad actors. In 2020, Oceana used the Global Fishing Watch map to pinpoint nearly 300 Chinese vessels fishing the waters off the Galapagos Marine Reserve, likely for squid, for more than 73,000 hours in just one month. Oceana also spotted some Chinese vessels that were disabling their tracking devices and engaging in other suspicious activities.

The exposé raised serious alarms around the world about the impact China’s massive fleet is having on the oceans. Back in Spain, Oceana used Global Fishing Watch data in its campaign to expand Cabrera National Park, an area south of Mallorca, home to rich marine life, including corals, dolphins, and whales. Oceana showed the area proposed for expansion was not heavily fished and would therefore not have a big economic impact on fisheries in the region. This helped make the case to the government, which officially expanded the park nearly tenfold in 2018, making it the second-largest marine park in the Mediterranean.

Broadening horizons

Despite its groundbreaking technology, Global Fishing Watch’s beginnings presented new challenges. “There were some areas where we didn’t have a lot of data because of where the satellites were located or because there was so much ship traffic that it was blocking out the fishing vessels,” Savitz explained. Another source of information — the vessel monitoring system (VMS) installed on some industrial fleets — could help fill in some gaps on the Global Fishing Watch map, but it was not publicly available.

VMS devices are tamper-proof, and they transmit a signal once an hour. They are typically more powerful than AIS and less likely to lose their signal, whereas AIS provides more real-time information. Together, the two technologies can work

in tandem to form an even more useful tool.

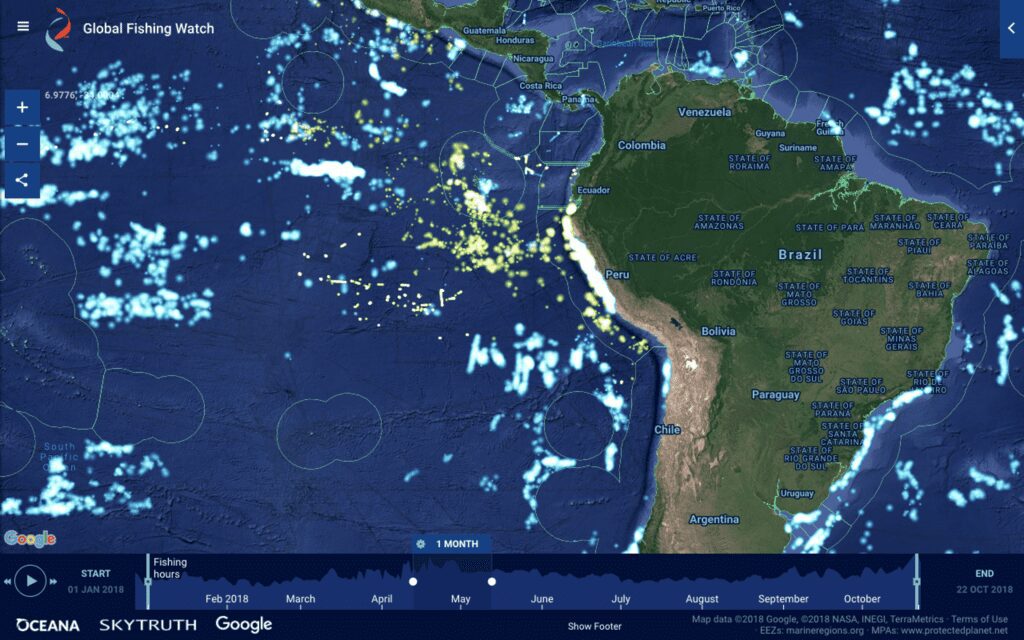

With this knowledge, Oceana used its proven campaign approach to persuade governments to share their VMS data and publish it on the Global Fishing Watch map. First, Oceana succeeded in Peru in 2017, when the government agreed to share its VMS data — making it the first nation in South America to do so. As one of the world’s most significant fishing nations, and home to an enormous anchovy fishery, Peru’s collaboration with Global Fishing Watch set an important precedent and made it easier to identify, track, and stop illegal fishing in Peru’s waters and empower the government to enforce its laws more effectively.

From there, Oceana was instrumental in securing a string of victories in Belize, Brazil, Mexico, and Chile, which all shared their VMS data with Global Fishing Watch. Additional countries that have already shared their VMS data with Global Fishing Watch include Norway, Benin, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Panama, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and Papua New Guinea.

“Transparency and collaboration are driving real change on the water, helping put an end to illegal fishing and other destructive practices,” said Tony Long, CEO of Global Fishing Watch. “As more countries share their vessel tracking data on our map, our global view of fishing activity comes into focus, enabling better ocean governance.”

Securing VMS data was just the tip of the iceberg for Oceana. “We have found so many ways to use data from Global Fishing Watch to advance our campaigns and win victories for the oceans,” Savitz said. Oceana has even used the Global Fishing Watch platform to create its own vessel tracking platforms: Ship Speed Watch, to monitor vessel speeds in areas where critically endangered North Atlantic right whales navigate, and Karagatan Patrol, which polices the waters of the Philippines to deter illegal fishing.

Slowing down to save whales

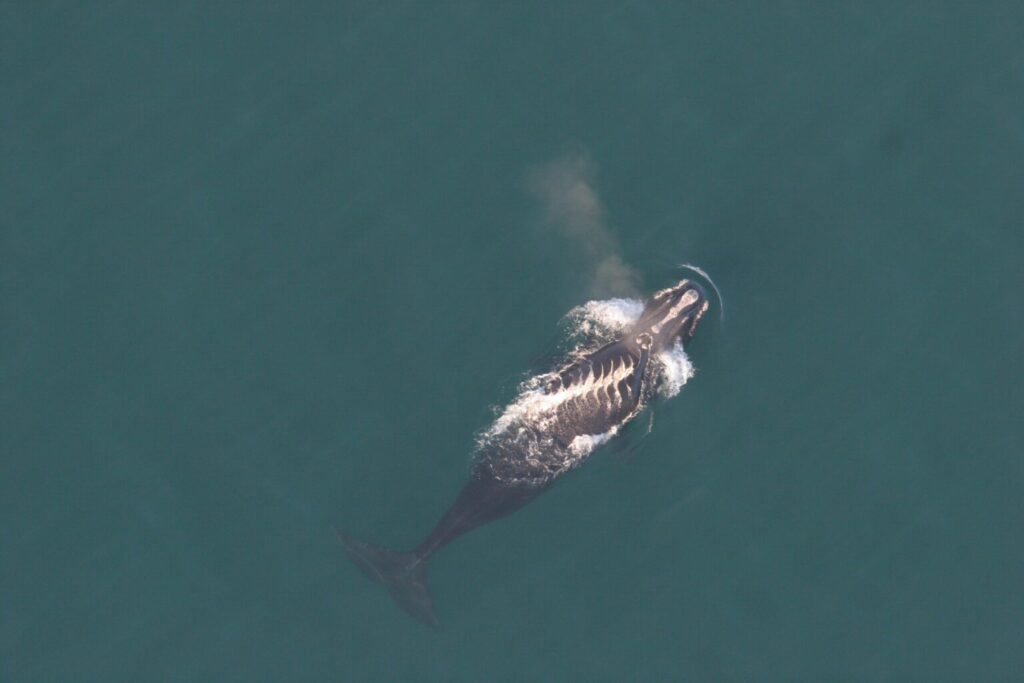

Since 2019, Oceana has campaigned in the United States and Canada to save North Atlantic right whales from extinction. Only around 330 of these animals remain.

North Atlantic right whales migrate seasonally from the northern Atlantic waters of New England and Canada to the warmer southeast Atlantic waters. The whales are dark in color and difficult to spot, swim slowly at the water’s surface, and lack a dorsal fin. Combined, these characteristics have put right whales in the direct path of two major threats: ship strikes and fishing gear entanglements.

At high speeds, vessels simply cannot maneuver to avoid these slow swimmers, putting the whales at great risk of being struck. A collision can cause deadly injuries from blunt-force trauma or cuts from propellers.

Slowing ships down could help reduce collisions with right whales, but many speed limits set by the U.S. and Canadian governments have been voluntary, leading to low compliance and an inability to conduct enforcement.

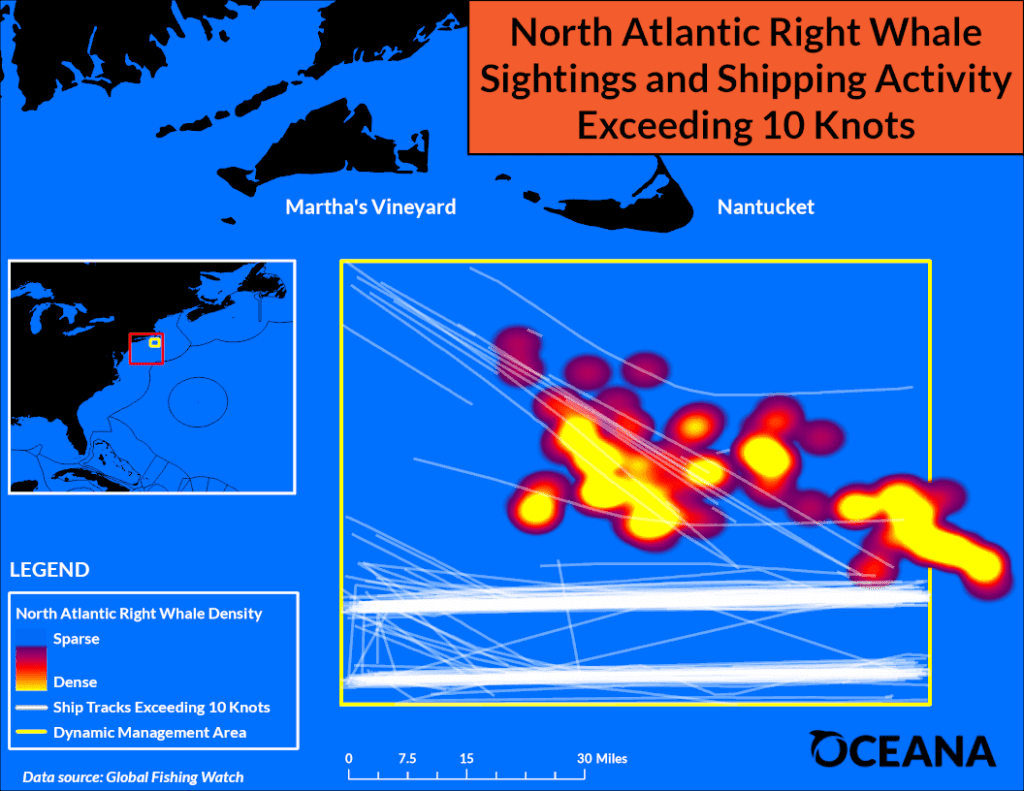

Using Global Fishing Watch data about vessel speed and direction from both fishing and shipping vessels, Oceana created a standalone platform — Ship Speed Watch — in 2020 to monitor ship speeds along the migratory route of the right whales. “Most of the speeding happens beyond the horizon,” Gib Brogan, Oceana Campaign Director, said. “Observing these vessels and checking for compliance with speed limits has been very difficult. Now with Ship Speed Watch, the public and government enforcement agencies can monitor speeding ships from their desk.”

Ship Speed Watch has proven to be a powerful platform, showing where vessels are ignoring the speed zones designed to protect right whales. In 2021, Oceana found that speeding boats are rampant throughout the whales’ route along the U.S. East Coast, in both the mandatory and voluntary speed zones. In Canada, though compliance is high in the mandatory zones, Oceana found this year that most vessels did not abide by the voluntary slowdown in a key right whale migratory area, the Cabot Strait.

“Ship Speed Watch has allowed us to paint a clear picture of this problem. We’ve been able to show both the U.S. and Canadian governments that their voluntary restrictions aren’t being taken seriously,” Brogan added.

And the U.S. federal government took note. After confirming Oceana’s data from Ship Speed Watch and verifying through their own analysis, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) released a new proposed vessel speed rule in July that aims to reduce the risk of vessel strikes to North Atlantic right whales. This updated proposal contains critical changes, such as including vessels greater than 35 feet in length (compared to the previous 65 feet), expanding seasonal speed zones, and upgrading current voluntary speed zones to mandatory in areas where whales are seen.

The proposed rule has undergone a public comment period, and when the final rule is published, enforcement will be key. Experts at NMFS say that to save the right whales, ship speed compliance needs to be close to 100%, Brogan added.

“We don’t want a marine mammal going extinct on our watch,” said Beth Lowell, Oceana’s Vice President for the United States. “With Ship Speed Watch and a strong new rule to slow down vessels, we are giving North Atlantic right whales a fighting chance at survival.”

Shining a bright light on illegal fishing

In the Philippines, commercial fishing vessels are known to encroach upon the country’s municipal waters, which are reserved for artisanal fishers. “It impacts the health of the habitats because some of the vessels use destructive fishing methods,” Danny Ocampo, Oceana’s Senior Campaign Director in the Philippines, explained. “The municipal and artisanal fisherfolk cannot compete with the technology, the gear, and the capacity of these commercial vessels.”

In some instances, locals have reported not being able to catch anything for a week or so after commercial fishing vessels enter their municipal waters. This means lost income and lost nutritious food. “We are considered one of the centers of marine biodiversity and nearshore fish species, but our fisherfolk are among the poorest of the poor in Philippine society,” Ocampo added.

When browsing Philippine waters on the Global Fishing Watch map, there is not much to see, especially when compared to other countries’ waters that have both AIS and VMS data available on the map. While vessel monitoring systems are now required on vessels in the Philippines, following campaigning by Oceana and its allies, the adoption of the law is still quite slow. VMS data is still held closely by the government and compliance is only around 50% of qualified commercial fishing vessels.

Despite these challenges, Oceana was keen to increase transparency in the Philippines. In 2019, Oceana teamed up with the League of Municipalities to create a new tool called Karagatan Patrol (“karagatan” translates to “sea” in Filipino) to empower fisherfolk, scientists, government officials, and other stakeholders to protect their municipal waters from illegal commercial fishing.

First, the duo created the Karagatan Patrol Facebook group to allow the public, fishers, and law enforcement to post information about apparent illegal fishing in their local waters. These instances are often recorded at night because the commercial fishing vessels with bright lights can be seen from shore. A post or message to the Facebook group — either by Oceana or members of the platform — would alert the enforcement agencies and local governments who have jurisdiction over municipal waters of the alleged activity, who could directly inspect the vessel’s activity.

These bright lights are also trackable by a technology called the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS), another satellite technology that captures visible and infrared images emitted by vessels at night. Access to VIIRS data was essential in taking Karagatan Patrol to the next level, said Jessie Floren, Oceana’s Database Administrator, who helped Oceana launch the accompanying Karagatan Patrol web application.

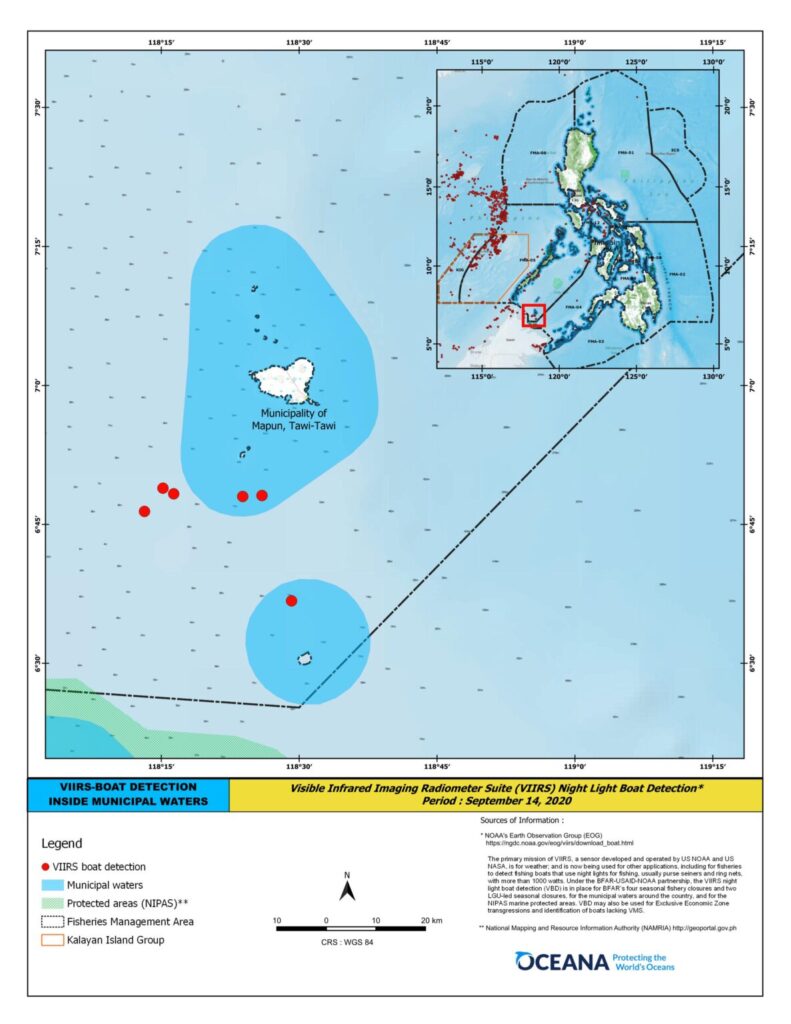

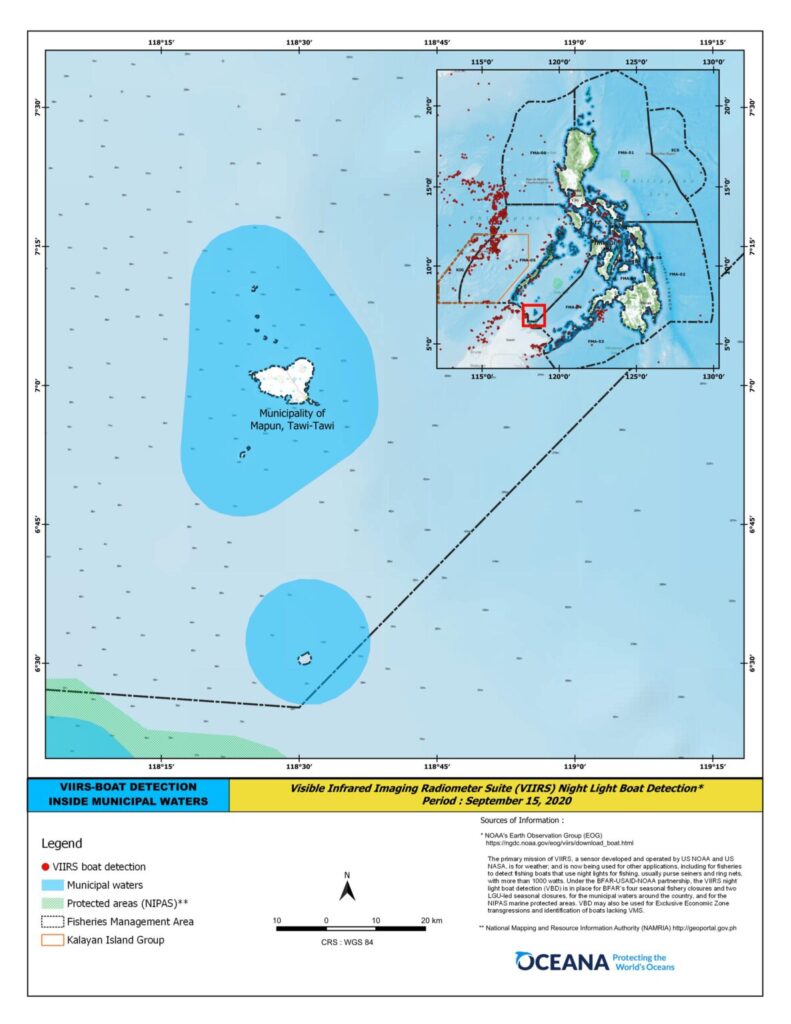

Oceana’s Karagatan Patrol, which tracks fishing vessels’ bright lights through satellites, reported commercial fishing vessels illegally encroaching on the municipal waters of Tawi-Tawi, as shown by the red dots in the map above, on Sept. 14, 2020 (left). Oceana quickly alerted local government officials, who apprehended the five vessels before the following day on Sept. 15, 2020 (right).

“We drew so much inspiration from Global Fishing Watch when creating this platform,” Floren said. The Karagatan Patrol map allows the public to see VIIRS data in Philippine waters in near real time. “With VIIRS data and interaction from scientists, fisherfolk, civil society organizations, and academia, we’ve created a really powerful tool.”

Data from Karagatan Patrol has been key in convincing national and local law enforcement and other governmental officials to reduce illegal fishing in their municipalities. Oceana sends a quarterly publication to local governments of the top “hot spots” where apparent illegal commercial fishing is most rampant.

In one instance, Floren recalled working with law enforcement in Tawi-Tawi, one of the southernmost regions of the Philippines that was consistently among the top 20 on Oceana’s illegal fishing hotspot list. Officials in the region were keen to take action and get their municipality off the list. Upon receiving near real-time data from Oceana, they were able to simultaneously apprehend about five commercial fishing vessels.

Endless possibilities

In just a few short years, Global Fishing Watch has shined a spotlight on fishing vessel activity around the world and has helped power Oceana’s campaign efforts to increase transparency, stop illegal fishing, and restore ocean abundance. From developing new tools like Karagatan Patrol that empower local communities, to saving megafauna at the brink of extinction, to protecting key marine habitats around the world, the possibilities and potential to be discovered on Global Fishing Watch seem endless.

“Global Fishing Watch raised the bar for everyone. Now fishing vessels are visible and it’s the norm,” Lowell said. “By building and acting on this information, we can increase transparency in fishing. That’s the way we’re going to have healthy oceans.”

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2022 issue of Oceana Magazine.

MOST RECENT

June 19, 2025

June 2, 2025

OPINION: From Crisis to Opportunity: Rebuilding Canada’s Fisheries for Climate and Economic Security